|

Shellfish Restoration

Network

|

Distributed by The Nature Conservancy's Global Marine Initiative

|

Seeking Input on a Global Shellfish Reefs at Risk Assessment

With funding support from The Kabcenell Family Foundation, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and partners embarked in 2007 on a global assessment of reef-forming shellfish – primarily oysters and mussel species – with the goal of better documenting their distribution, condition, and the threats that they face across the globe. Management of shellfish ecosystems has historically been undertaken on a bay-by-bay basis and, as a result, there is often little understanding of or appreciation for shellfish reefs and beds as a globally significant type of ecosystem. With the collapse of shellfish fisheries in many parts of the world, and the array of pressures placed on coastal ecosystems generally, shellfish ecosystems may in fact be among the most imperiled of all coastal marine ecosystems. By addressing shellfish condition and data on threats at large scales, the Global Shellfish at Risk Assessment is intended to help catalyze actions that are important for both conservation and sustainable fisheries management. Underpinning the project is a synthesis of the readily-available spatial data on distribution and condition of habitat-forming bivalves. In Phase I of the Assessment, distribution data were compiled by experts from China, Europe, South America and the United States and assembled into a global geodatabase. Extensive data were also provided by the Ocean Biogeographic Information System. This database will help to illustrate the extent of shellfish reefs and beds on a global basis. In Phase II, condition data is being gathered through a survey of experts as well as simultaneous review of the literature to illuminate the historic and current condition of shellfish reefs throughout the world. We are actively seeking additional survey data through an online survey, which takes approximately 15-20 minutes. If you or colleagues have direct knowledge of habitat-forming shellfish in a bay or several bays, we would greatly appreciate your input through this short survey. The data collected through the surveys will be compiled and synthesized in a “Shellfish Reefs at Risk” report to be published in late 2008, and will be included in the geodatabase that will be made broadly available for management, research and conservation partners. If you have questions or would like to know more, please contact Rob Brumbaugh. Back to top » |

One significant departure from the past is the panels’ acknowledgement that separate management approaches will be required to meet the dual goals of improving ecosystem health and providing fishery benefits. To improve ecosystem health, the panels are seeking to expand restoration to a scale that allows native oysters to provide their many natural services, which requires both improved targeting of restoration actions and increased and sustained sources of funding. Scientists briefing the panels have noted oysters in one tributary that has been closed to harvest for more than a decade has resulted in more resilient and disease-tolerant oysters. Therefore, a recommendation for both states is for increased use of sanctuaries that would help oysters develop natural tolerances to devastating diseases that have reduced populations in recent years. Another recommendation, given the limited amount of clean oyster shell available for restoration, is to explore alternative materials as a means of increasing the area of restored reefs. Such practices are increasingly common from North Carolina to Texas, but have received less attention in Virginia and Maryland. Although fishing traditions differ somewhat between the two states, both panels recognized that the best opportunity to expand the economic production of oysters lies in privatization and aquaculture. In the short-term however, both panels also recognize the needs of existing watermen who are used to a public access fishery. Each state is considering facilitating opportunities for watermen to transition to aquaculture and, in Maryland, establishing a system of privately leased oyster bars (which already exist in Virginia). Furthermore, Virginia has created a pilot management approach in one river which seeks to ensure stable harvests through rotating harvest areas. With the decline of native oysters, some in the Chesapeake Bay community have looked to a species of non-native Asian oyster (Crassostrea ariakensis) as a “silver bullet” for rebuilding the bay’s oyster fishery. Neither panel has dealt explicitly with the Asian oyster issue, as the Army Corps of Engineers is leading an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) which seeks to address the potential ecological and economic impacts of an introduction. In the meantime, however, a bright point has emerged with the native oyster in recent aquaculture trials sponsored by the oyster industry and the state of Virginia. These trials have used native oysters in sterile (triploid) form and are finding survival rates equal to or better than other species in major oyster industries worldwide. Further, research associated with the Asian oyster EIS emphasizes that there is no quick fix to the problems of low oyster populations in Chesapeake Bay. The research indicates that the Asian oyster is highly susceptible to diseases to which the native oyster apparently is immune—diseases likely to spread to the Chesapeake Bay in coming years—as well as more vulnerable to the poor water quality found in the bay than the native oyster. For more information about recent research on Crassostrea ariakensis, visit the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office website. Looking to the future, the recommendations from both panels underscore the need for long-term investments to address water quality problems and oyster restoration to achieve ecological and economic goals for the native oyster. For more information, please contact Mark Bryer, who serves on the Maryland Commission, and helped represent The Nature Conservancy on the Virginia Panel. Be sure to check out the final report from Virginia’s oyster panel and the interim Maryland oyster commission report.

Global Review of Marine Invasive Species

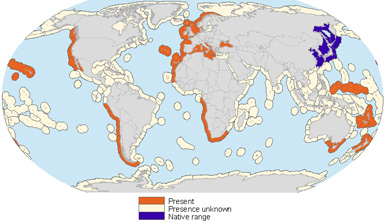

A new Nature Conservancy study is the first global review of marine invasive species. Led by scientists in The Nature Conservancy’s Center for Global Trends and published recently in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, it documents 329 species – where they are, how they got there, and which ones are most harmful. The results of the study show that the threat of marine invasive species is widespread – 84% of the world’s marine ecoregions have been invaded by at least one species. Preventing introductions is key in addressing the threat of invasive species, as once a non-native species is introduced and becomes invasive, it is almost impossible to remove it. The study identified top global pathways responsible for invasions. Shipping (including via ballast water and bio-fouling) was the most common pathway of species in our study (69%). Aquaculture was the next most common species pathway (41% of species). Some of these aquaculture introductions of nonnative species were intentional for cultivation. Many others were introduced accidentally, hitchhiking on farmed species or equipment. In the U.S. these introductions mostly occurred prior to the development of modern hatchery-based approaches and permitting requirements that are intended to significantly reduce these risks. In addition, guidance provided by the International Council for Exploration of the Seas Code of Practice on the Introductions and Transfers of Marine Organisms adopted in 2004 is intended to further reduce the risk of future invasive species introductions from aquaculture. One of the most widely spread intentionally introduced species in the study was the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas). It is present in at least 45 coastal ecoregions outside of its native range (see map) and in some regions it has caused significant economic and ecological harm. For example, it was introduced in France in the 1970s, and has since spread north into the Wadden Sea, despite predictions that it would not survive in the cold waters. Here the Pacific oyster is colonizing on and replacing native mussel beds - an important fishery in the Netherlands. Not only are the mussels being lost, but native birds that depend on the mussels are at risk and the oysters are not as economically viable as those cultured in cages elsewhere in the region. This study gives the

first global picture of the extent of the threat of marine invasive

species, and also provides tools that can help inform strategies for

preventing new invasions. Cultivating Conservation – Advancing Shellfish Restoration in Collaboration with the Aquaculture Industry

Restoration Restoration of native shellfish reefs and beds is becoming a high priority for many conservation groups, management agencies and the general public. Although shellfish reefs have long been recognized as an important habitat for fish and other species by biologists and fishermen alike, only recently has there been a movement to restore and manage them specifically for their habitat value and ‘ecosystem services’ other than direct harvest. In the past 10 years, however, scores of shellfish reef restoration projects have been undertaken around the U.S. for a variety of species including hard clams, eastern oysters, Olympia oysters, bay scallops and blue mussels. Many of these projects have been funded through programs like the NOAA Community-based Restoration Program and were designed to test restoration approaches at modest scales and increase public awareness of the ecological role that native shellfish play in coastal bays and estuaries. As restoration techniques are tested and refined there is an increasing desire to undertake restoration projects at larger, more ecologically meaningful scales. To accomplish this requires an industrial-scale capacity that partners in the aquaculture industry can provide to help address various logistical challenges. In the U.S., conservation groups such as The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Puget Sound Restoration Fund, Chesapeake Bay Foundation and others have been collaborating with the shellfish industry to undertake large-scale broodstock enhancement using hatchery-produced shellfish and physical restoration of reef habitat. In these collaborations, the conservation community often provides the overall project leadership and assumes the responsibility for monitoring and assessment of the outcomes, while the industry provides logistical support with hatchery capacity, barges and other expertise needed to deploy large volumes of shell substrate to restoration sites. In the Puget Sound in particular, the shellfish aquaculture industry has a long history of partnering with TNC and other NGOs on initiatives to restore and protect water quality around restoration projects and their farms. Rob Brumbaugh, Restoration Program Director

for TNC’s Global Marine Team, presented an overview of these kinds

of collaborations in an industry forum called Farmers Days at the

recent International

Conference on Shellfish Restoration (ICSR) in The

Netherlands. From the response of the largely European

audience, such collaborations appear rather unique to the U.S. at

this point, but hopefully serve to inspire such projects and

interaction elsewhere. Looking Ahead National

Shellfisheries Association 100th Anniversary

Conference, April 4-8, 2008 TNC-NOAA Community-Based Restoration Partnership is soliciting proposals for restoration of marine ecosystems across the U.S. and its territories. Deadline for proposals is March 28, 2008. For more information visit the NOAA Restoration Center Website or Email Boze Hancock, TNC-NOAA National Partnership Coordinator. American Rivers-NOAA Community-Based Restoration Program Partnership seeks proposals for river restoration project grants as part of its partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Community-based Restoration Program. Projects in the Northeast (ME, NH, VT, MA, CT, RI), Mid-Atlantic (NY, NJ, PA, DE, VA, MD, DC), Northwest (WA, OR, ID), and California are eligible to apply. Projects located within the St. Lawrence/Great Lakes Basin are not eligible for funding in the April 2008 grant round. Applications are currently being accepted for the second cycle of fiscal year 2008 with a deadline of April 1, 2008. Obtain the Application for Financial Assistance and Funding Guidelines on the American Rivers Web site or Email Serena S. McClain. The Practitioner’s Guide to Shellfish Restoration: An Ecosystem Services Approach, as well as back issues of the Shellfish Restoration Clamor are available online. Cool Video! Common Ground by Chesapeake Bay Foundation Guidance on methods for monitoring oyster reef restoration projects is available at the Oyster Restoration Workgroup website. | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||